Why do we care about what we care about?

Muse #522 - passion, desire and irrational attractions

There are lots of things we care about. We care about taking care of ourselves in a variety of ways. We care about people around us both in our familial and social structures. We care about things. The mundane to things that we associate value by ourselves - things that we value because others value them in a variety of ways.

All this thought was triggered by one Epictetus quote that I read this morning:

Passions stem from frustrated desire — Epictetus

Passion for what? And a frustrated desire for meeting that passion and to what end? That led to more research on this topic.

And I found this explanation:

The origin of perturbation is this: to wish for something, and that this should not happen.

This is one of the most well-known principles of Stoicism - if we desire things outside of our control, we get frustrated when we don't get them. When we focus on our own actions and judgments, we control them, and they can always be as we want them to be.

It's interesting how different translation changes the meaning. Passion is somewhat positive, while perturbation definitely is not. Then again, the word perturbation is not often used, while passion is.

And that was not the end of it. The search furthered with additional interpretations of the word “Perturbation” and “Passion” as below:

Desire or craving is irrational appetency, and under it are ranged the following states: want, hatred, contentiousness, anger, love, wrath, resentment

While some translations use "desire" as a neutral word, I feel that it's better to use "desire" and "attraction" separately. This way desire means "irrational attraction", as opposed to wish which is rational.

"Passion" was used by Stoics to define something like a strong emotional state, or disobedient to reason. Most of the passions were considered irrational, and based on a mistaken perception, or a falsehood - some examples are anger, hatred, or fear, but also depression or compassion (important note - this applies when compassion is exceedingly strong, and cannot be controlled by reason). That's why we can usually read about getting rid of passions in the Stoic writings.

Ah. Figures. I guess. And then I finally ended up at the Wikipedia on Stoic Passions.

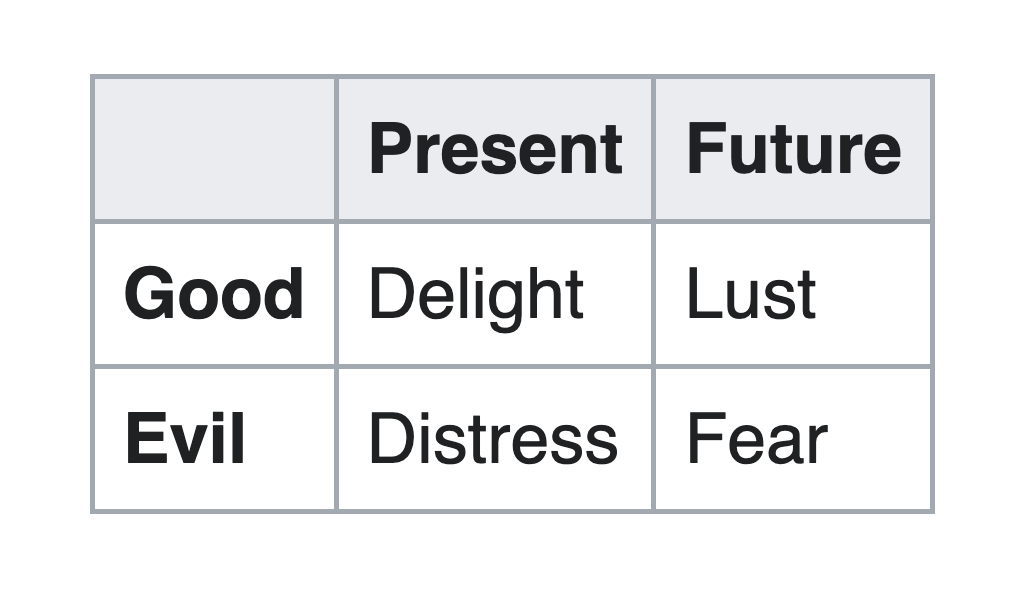

The Stoics beginning with Zeno arranged the passions under four headings: distress, pleasure, fear, and lust.

Distress (lupē) - Distress is an irrational contraction or a fresh opinion that something bad is present, at which people think it right to be depressed.

Fear (phobos) - Fear is an irrational aversion or avoidance of an expected danger.

Lust (epithumia) - Lust is an irrational desire, or pursuit of an expected good but in reality bad.

Delight (hēdonē) - Delight is an irrational swelling or a fresh opinion that something good is present, at which people think it right to be elated.

Two of these passions (distress and delight) refer to emotions currently present, and two of these (fear and lust) refer to emotions directed at the future. Thus there are just two states directed at the prospect of good and evil, but subdivided as to whether they are present or future:

So why do we care about what we care about? These four reasons finally looked like they explain it. Or does it?

Stoic passions — https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stoic_passions